When I have time on a spring evening to take the old Honda Shadow for a spirited cruise on local country roads, there are two stops I always make on the way back home. One is for the way it looks, the other for the way it sounds.

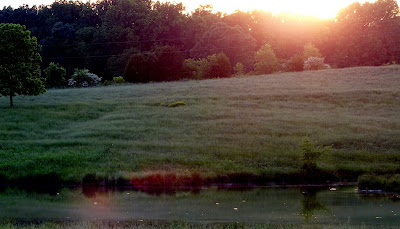

The first place has the most vivid sunsets I have been able to find in this part of central North Carolina. Having photographed sunsets in all 50 states and on four continents, I should have seen enough of them, but I’m still a sucker for even the lackluster ones we have in these parts.

This particular location tugs gently because it resembles a view I enjoyed many times, over four decades, near my family’s original home place in Upstate New York, near the shore of Lake Ontario. There is no such huge lake here, of course, not 20 minutes west of Chapel Hill, but there is rolling terrain, and a couple of large farm ponds. It doesn’t really do, but it has to.

|

| Central North Carolina sunsets are basically pathetic; this farm pond scene is the best we have locally, and it is at least worth an evening motorcycle ride |

|

| In fairness to North Carolina, since I am used to sunsets like this over Lake Ontario in New York, all sunsets have a tough act to follow |

When I ease to the side of the road, kill the motor, and take off my helmet, there are at first no sounds except for a distant frog and a few buzzing insects. Within a couple of minutes, more frogs start calling—sounding as if they are practically under my riding boots. Then come the sharply accented notes I wait for: Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

There is no gentle tug to this. There is instead a rush of memories.

I am eight years old and standing with my brother-in-law Harold at a farm pond in Craig County, Virginia. In my eyes the greatest thing my oldest sister ever did was marry Harold, who grew up on the farm that surrounds this pond. As dusk falls we cast top-water poppers and twitch them back toward us. In the failing light, largemouth bass smash the lures and make acrobatic leaps, and whip-poor-wills call all around us. The fish aren’t big, but the haunting calls from the blackness enveloping us carry all the excitement a child can handle.

Harold tells me the myth of the whip-poor-will as a goatsucker, that being a family of birds that got their name from allegedly feeding on goats’ milk at night. He greatly embellishes for my benefit. Even my pea brain registers that these birds are not sucking a living from goats, because Harold’s family raises cows, but it is still a great story.

|

| A night-jarrer [photo from Wikipedia] |

I am 14 and am sitting by Carvins Cove, near Roanoke, Virginia, as my father and I wait for our quarry—channel catfish—to move onto the shallow feeding flat where we have cast our bait. My father has the proverbial patience of Job when it comes to fishing. I do not. I began fly-fishing at age 10, because it provided movement and kept my hands busy. But I also like to catch fish, instead of just sitting. After fly-casting for trout feeding on the last caddis-fly hatch of the evening, I put aside my fly rod, sit on the other side of a kerosene lantern from my father, hold a spinning rod, and wait. And wait. The whip-poor-wills are nearly deafening as they call all around us. Every few minutes the line twitches and I crank in another catfish, but the real appeal of the evening is quality time with a father who I otherwise do not connect with, in the mysterious darkness near an old and very spooky cemetery, feeling like we could just as well be sharing this moment hundreds or thousands of years earlier in a far more exotic locale.

I am 22 and my uncle Carl and I are sitting under a half moon in his tiny, 12-foot aluminum canoe, fishing rods in hand, in a narrow section of Sandy Creek that is separated from the crashing waves of Lake Ontario by only a 20-foot-wide spit of land. The walleye and bullhead are running in from the lake and we are stocking the freezer for Carl and my aunt Emma. The whip-poor-wills are raucous in their approval—until I hoist a foot-long bullhead from the creek and a 19-pound northern pike erupts from the black water, smashes the bullhead, and lands in the canoe, thrashing crazily. A northern pike that big, that close, and that unexpected makes one’s brain scream “alligator!” Carl and I both blame the other for screaming like a little girl. With the pike subdued and our laughing and teasing subsided, we return to catching smaller fish, and the calls resume. Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

I am 45, eight years removed from nearly being killed by a medical mishap, three years beyond the end of a first marriage, one year nearly recovered from being badly banged up in a bit of foreign street-riot nastiness, and I am living in a small cabin in a nature preserve, by a five-acre lake. In the rush of travel, the real life of being married, the unreal life of being nearly dead and mostly back, I don’t think of goatsuckers for a decade. On a warm spring evening I walk out to my back deck, shot glass of Scotch in hand, and hear long-forgotten notes trill across the little lake: Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

Realization hits me: a half-mile beyond the other side of the lake is the dirt road, now paved, my dad used to drive to get to the lake where we caught catfish by the light of a kerosene lantern. I recall the ride home in the dark, seeing the bright red eyes reflect in the weak headlight beam of a ’52 Chevy, and remember straining to see the birds launch from the dirt road and fly away as we approach. These birds are descended from those birds, and I am descended from that kid, even if I can barely remember him.

“This is home,” I tell myself. “This is where I make my stand, and finally get back to writing.” And I do, for two glorious years—having traded a Washington, DC townhouse for a cabin the size of my former living room, and social swirl and senate hearings for time with some half-wild cats, a half-tame black bear, and a herd of nearly domestic deer. Instead of running “The Mall” in DC I run the trail around the lake and into the mountains beyond. Women my age come to this lake. More importantly, so do their adventurous 20-something daughters, who like to run the trails with me, and hang out at the cabin for hours, and sometimes days, at a time. The trade from DC to here is one I become very happy about.

And then planes fly into buildings. I suddenly find myself again based out of DC, photographing and writing about the uproar there and beyond. The insanity that follows takes me places I couldn’t even find on a map a couple of months earlier. I learn where Yemen is, and that in one rapid dash across the Horn of Africa it is actually possible to be airsick, seasick, and carsick all in the same day. What a weight-loss plan, even more effective than trail running and spending as much time as possible with 20-something women. I learn that in some countries, if someone pulls a gun and tries to block the way, the driver just runs them over—but he has to use enough finesse to hit them solidly enough with the fender to knock them down, but not with the bumper, or they go under the truck. It is very difficult—and messy—to extract them from the undercarriage when that happens. I learn that people are more polite in Zimbabwe, where they all seem to be packing heat, than they are in DC, where there are all kinds of laws against packing heat. I learn that if you actually enter the building at the border to Congo and ask them to stamp your passport, you either pay bribes, or endure threats against your life and maybe a few hours behind bars—or you just sit outside and wait for some Rwanda military guys to show up with machine guns, and you just smile at the border guard as you follow them through. I also learn that when you go out for a trail run in Kenya, and you hear a lion roar, it is really dumb to assume it is probably in a zoo—and that I can still climb trees almost as fast as when I was a kid, if the adrenaline is pumping.

And I don’t think about goatsuckers for a decade. Until a month or so ago, running the road that twists by our house, under the light of a full moon, wishing the woodcock could have stayed a little longer and the huge coyote, or red wolf, or whatever it is I have seen twice would come out in daylight when I actually have a camera in hand, and I hear ghostly notes trill through the darkness: Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

I stop dead. For the first time in a decade I think about the past that is now so far past it is a blur, the planned future in California that even at my age lies so far ahead I can’t even fathom it, and I savor the memories carried by the calls ringing through the night. Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

“This is home,” I tell myself. “This is where I make my stand, and finally get back to writing.”

Late that night I stand in front of my laptop, which rests on the tall work bench on our screened lanai, and I give the writing a shot. The old lantern, veteran of countless fishing trips of my youth, swings overhead. A glass of Scotch sets within easy reach to the right of the keyboard, and a couple of mostly tame cats loll to the left—their ears twitching as haunting calls from the surrounding darkness voice raucous approval. Whip-poor-will! Whip-poor-will!

_______________

Copyright © 2013 by motomynd

| Please comment |

Moto this is great piece of work. It took me back to my childhood. My great grandmother told me, the whip-poor-will was scolding the cats for the birds they had killed. There were none in Northern Mississippi where I lived, and I don't remember hearing any back on the farm, although they were everywhere in the 50s. The DDT may have killed them off as it did a lot of things in the south. In my mind I can hear them now, as I sat on the front porch listening to that wonderful old woman tell stories. Thanks for the memories.

ReplyDeleteKono, thank you for sharing those thoughts. Many whip-poor-wills spend their winters down your way, so if you find the right place, you may be able to hear that call again.

DeleteNative cultures around the world have many beliefs about animal totems and what they mean to us. I have to wonder if "goatsuckers" are my totem, because wherever I encounter them, they always seem to pull me back toward a center that life all too often tries to spin away from. Even though I didn't mention it in the post, I saw nightjars in Kenya at a time I was thinking of permanently moving there, and I was immediately reminded of how much I was not quite ready to give up in America. Even though the move was, and still is, at times very tempting.

even a die-hard city gal gets this, lovely, thanks

ReplyDeleteThank you, Susan. I have no idea which city you may be a die-hard for, but it most likely has fairly near it a cushy lodge in the not-too-distant boondocks, where one could enjoy the calls of the nightjars along with five-star service and lodging.

DeleteMotomynd, while I think that "basically pathetic" is a way-over-exaggerated put-down of North Carolina sunsets (I've seen glorious ones from my back porch in Mebane), I much enjoyed another of your radiant memoirs and particularly love the way you're holding little back, not only from your inner communings with nature, but also from your action-packed life on photographic (and it sounds like other) assignments around the world, including, this time, a caption for that intriguing photo of you behind those designer bars! As always, this blog's editor in chief is deeply grateful that you let him publish your outstanding work here. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Morris. Just trying to keep up with your other far-flung, world-traveling writers. As for those "glorious" North Carolina sunsets you mention...hmmm...how about posting a photo essay sometime? Looking inland from the barrier islands I have seen some memorable sunsets over the North Carolina bays and inlets, and a few in the Blue Ridge mountains, but I think I would have to stretch my "Top 100" list to "Top 1,000" to include any I've seen in Central North Carolina.

Delete