From ghoulies and ghosties

And long-leggedy beasties

And things that go bump in the night,

Good Lord, deliver us!

Halloween evokes a memory of parties put on by the PTA at the rural schools where my father was the principal. The current incarnation of the holiday strikes me as a commercial enterprise, a marketing device without a tradition or adventurous spirit for kids. Instead of a shared effort among adults to create childhood memories of scary fun, much has been leached away by creeping institutional control.

Then was a world of bobbing for apples, pumpkin cookies, caramel apples, a “fright booth” more fun than scary, costume contests, and a storyteller with ghost stories for the younger kids. The old lost America that makes for 1950s nostalgia was rural communities coming together to make it happen year after year. When I lived in a small town, toward the end of the Fifties, another custom I shared was Halloween “Trick-or-Treating” door to door, with most of the neighborhood handing out treats for kids dressed in costumes their mother had improvised. I recognized as an adult that this was as much an event for the grown-ups as for the children as I watched my mother, a retired school teacher, excitedly prepare to greet trick-or-treaters.

As a 1960s art college student in San Francisco, I encountered another aspect of Halloween – the opportunity to assume a disguise and live for an evening beyond the mundane. That’s an even older tradition: Brazilian Carnival, New Orleans Mardi Gras, the Roman Saturnalia – a culturally protected space for breaking loose. Now, as police and city administrations declare a “war on fun,” with attempts to shut down Halloween in Greenwich Village and San Francisco’s Castro, institutionalization and commercial interests seek command of the last day of October and the community aspect is getting lost.

Samhain was the Celtic Beginning of Winter festival, considered the start of a new year: a time for taking stock, literally of herds brought down from Summer pasture, and for Divination – looking to future prospects. At least that’s the “Celtic Revival” interpretation of 19th and 20th Century Irish writers – a mix of myth and stories that survived Ireland and Scotland’s being “Christianized.” Now we have on October 31st and November 1st and 2nd All Hallows’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day. Established by Pope Gregory III, these are examples of Pagan rituals being transmuted to forms of the Church of Rome.

Growing up in the central valley of California introduced me to another tradition. Dia de los Muertes, the “Day of the Dead,” Mexico’s celebration of family memories. For an outsider to the community, their images of skeletons invoked Halloween. Anyone familiar with Mexican art, whether visual, cinematic, or in literature, encounters death as a major theme. History reinforces that perception; whether in the Aztec, Conquistador, or Revolutionary eras, blood and suffering were a reality. The origins of the Day of the Dead are unclear. Some sources tie it to Aztec ceremonies. However, the thorough trashing of pre-Columbian cultures throughout the Americas by the Church and Spanish colonial governments make that debatable. Further, the link to Catholic Saints Days and a focus on family history and ancestors suggests something of a more gentle civil origin.

In contemporary Mexico, taking the day to sweep the graves and provide gifts for the dead by having a family meal at the cemetery and leaving bouquets of marigolds (an Aztec symbol of death) is a mix of tradition and popular culture. Defiant rather than morbid are the practices of eating sugar skulls, having puppets and costumes of dancing skeletons, and stylizing images of both. In Mexico and Latin America, affirming life and survival seems to me the real meaning of Dia de los Muertes.

In the United States in the second decade of the 21st Century, Halloween has lost its spirit. I’m tempted to mark that point from the original John Carpenter Halloween movie of 1978. In the decades since, the holiday has been made more menacing by a mixture of TV news stories about tainted candy, police spokesmen interviewed on the evening news warning parents to avoid risks, and “helicopter mothers.”

Commercialization seems to increase every year. Right now, my local dairy has a haunted house on its chocolate milk cartons, and Netflix mailers have ghosts flitting about. Again this year, as for the last four or five, a Halloween Superstore has set up in one of downtown’s vacant storefronts flogging ready-made costumes, bats, spiders, jack-o-lanterns, and cobwebs. A recent headline on the IO9 website was “The Geekiest Baby Halloween Costumes from All Over the Internet!” (I’ll admit the costumes and kids were cute.)

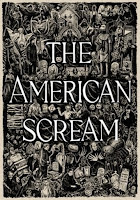

The American Scream, a documentary about three families in Massachusetts who devote most of the year to creating what looks like a fun Halloween experience, is due out for the holiday. Whether they represent signs of a change in approaching the holiday or are just charming eccentrics, it’s hard to guess. More of this kind of imaginative maker-oriented effort, and less focus on the buck, would be good to see.

Basically, this has been a “nostalgia ain’t what it usta be” essay. Perhaps it’s a function of my age, or the failings of the age, but I see a loss of a quality of wonder that Halloween used to possess. The old Scottish prayer that fronts this piece held a sense of wonder along with a sense of fear. There’s a sense of diminishment these days.

I’m not suggesting a turn to religion here – or worse, to superstition (even in the pop culture form of the Twilight movies) – rather a recovering of Halloween whose keystone is imagination and engagement in life. We need, borrowing from Morris Berman’s 1981 book, a “re-enchantment of the world” so that we savor its wonder.

In the United States in the second decade of the 21st Century, Halloween has lost its spirit. I’m tempted to mark that point from the original John Carpenter Halloween movie of 1978. In the decades since, the holiday has been made more menacing by a mixture of TV news stories about tainted candy, police spokesmen interviewed on the evening news warning parents to avoid risks, and “helicopter mothers.”

Commercialization seems to increase every year. Right now, my local dairy has a haunted house on its chocolate milk cartons, and Netflix mailers have ghosts flitting about. Again this year, as for the last four or five, a Halloween Superstore has set up in one of downtown’s vacant storefronts flogging ready-made costumes, bats, spiders, jack-o-lanterns, and cobwebs. A recent headline on the IO9 website was “The Geekiest Baby Halloween Costumes from All Over the Internet!” (I’ll admit the costumes and kids were cute.)

The American Scream, a documentary about three families in Massachusetts who devote most of the year to creating what looks like a fun Halloween experience, is due out for the holiday. Whether they represent signs of a change in approaching the holiday or are just charming eccentrics, it’s hard to guess. More of this kind of imaginative maker-oriented effort, and less focus on the buck, would be good to see.

Basically, this has been a “nostalgia ain’t what it usta be” essay. Perhaps it’s a function of my age, or the failings of the age, but I see a loss of a quality of wonder that Halloween used to possess. The old Scottish prayer that fronts this piece held a sense of wonder along with a sense of fear. There’s a sense of diminishment these days.

I’m not suggesting a turn to religion here – or worse, to superstition (even in the pop culture form of the Twilight movies) – rather a recovering of Halloween whose keystone is imagination and engagement in life. We need, borrowing from Morris Berman’s 1981 book, a “re-enchantment of the world” so that we savor its wonder.

| Copyright © 2012 by Tom Lowe, 2020 by Moristotle Tom Lowe was a founding contributing editor when the blog Moristotle transitioned to Moristotle & Co. Death took Tom from us on October 24, 2014. |

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment