Across the genres:

from the mythical west to the dystopian future

By Jonathan Price

The films A Million Ways to Die in the West, Chef, Palo Alto, Locke, and The Rover represent ones I’ve seen within the last month, and they merit some attention, even if you decide not to see them. But each seems to represent a different genre, or a different tendency in filmmaking, and a different tendency of some creative people to move off in new directions, but most still remain disappointing in some way.

In A Million Ways to Die in the West (2014, directed by Seth MacFarlane), the title seems to encompass the plot; and it’s obviously a Western, but the Western, like the dying West, is a dying genre, only it’s been dying for a long time. The first American feature film was a Western, The Great Train Robbery (1903). At the very beginning of filmmaking when writers, cameramen, directors, and audiences were still trying to create, delineate, and appreciate this startling new development in technology, it was silent, only 10 minutes long, “based on a true story,” and in New Jersey, with its spindly birches – not an iconic Western landscape with mountains and deserts. This was some 30 years before the Western became an iconic, mythic form, almost a ritual or sacrament and a mainstay of film narratives for three decades. The West to which it had referred had begun to atrophy soon after the Civil War’s end in 1865 and was pretty much a dead issue by 1890, some ten years before its first cinematic version.

But one key element in the Western is nearly always nostalgia – loss and longing. Some of its other constituent narrative and visual elements, which you may recognize from your childhood and the following list, which are duly ticked off in A Million Ways to Die in the West: long rides across barren spaces on horseback, set against a backdrop of monoliths (often from Arizona’s Monument Valley, as if they were scenery dragged out at Western movie-making-time), climactic gunfights (this film has three), a race between a train and horses, sheepherders, Indians, the hero gets the girl. A Million Ways parodies all of these, deconstructing them but going far beyond the American revisionist Westerns of the late 1960s (think of The Wild Bunch, 1969, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, 1971, even Blazing Saddles, 1974) into superficial sarcasm and ultimately sophomoric humor – fart jokes and references to fellatio and anal intercourse supposedly replace plot, theme, and, sadly, entertainment.

The trouble with this brand of humor is that it appears to be thrown in to show how hip the film is, how it doesn’t believe any of the myths. Instead it is often irritating, or just juvenile or silly. But it does have an unusual performance by Charlize Theron as the gunslinger’s sympathetic (to the hero), yet bitter wife, and Theron has said she was dying to get the role. The film was written, directed by, and stars Seth MacFarlane. Its other noteworthy feature is a series of cameos by various actors, usually placed for their anachronistic value in deconstructing the Western itself – Jamie Foxx as Django in an antiracist killing tucked into the credits, Bill Maher in a comic bit, a figure from Back to the Future discovered in a garage, Wes Studi as Cochise.

Chef (2014, directed by Jon Favreau) is – guess what? – a movie about food and making it. The title suggests a documentary, but we get a quirky independent feature film about an innovative, talented chef trying to save his Los Angeles restaurant’s class without alienating his boss, the owner (Dustin Hoffman), for whom profits come first. The first third of the film is exciting, enthusiastic, with collages of the chef buying food, sampling techniques, preparing it, and delighting his staff and friends with samples – even seducing his much younger hostess, played by Scarlett Johansson, with a food preparation that subtly borders on the erotic, and makes us wish we there…to sample the food. He also has an intriguing relationship with his son and ex-wife (who, contrary to type in divorcee films, is totally supportive).

And then the film breaks down into renewed (supposedly) gourmet enthusiasm with a new project to purchase a very used food truck in Miami and drive it across country cooking Cuban sandwiches in key locales, such as New Orleans. This fails in two ways at once: the clientele may be enthusiastic, but apparently they are all tasting the two or three items of cuisine served by the truck – this doesn’t mesh with the chef’s gourmet enthusiasm and innovation; the city by city locations required by the geography of America (from Florida to California) present no development of theme, character, or even urban character; it’s as if we’re watching a boring reality show. And the film trails off in predictable ways.

Palo Alto (2013, directed by Gia Coppola) is an opaquely titled film that was (probably) shown in all of seven theaters across America. Supposedly set in Palo Alto, California (though it was shot in Southern California locales) and based on a collection of short stories with the eponymous title by James Franco, who also acts in a key role, the film is a series of coming-of-age vignettes about a predictably dysfunctional group of teens without genuine adult guidance. Despite the fact that Stanford is just around the corner (though in its own municipality) and that Palo Alto itself is in the center of Silicon Valley with several certified billionaires lining its city streets, there seems to be no interest in class, sociology, microchips, or even much sense of location. Palo Alto, Spanish for “tall stick” is supposedly derived from a stand of redwoods last seen two centuries ago; no one connected to the film seems to be concerned with this origin either. There are instead a lot of short sticks and immature characters around.

The only thematic given is the failure of father figures, including but not limited to the soccer coach/teacher at the local high school, played by Franco, who seduces his teen star and babysitter April, the sensitive figure in the film who, sadly and perhaps inevitably, is dismayed when she finds her seduction is part of a player-babysitter seduction succession. There are, surprisingly, few fathers to be found, though supposedly Silicon Valley is overpopulated by successful young males (compared to females). One father invites his son’s male friend in, proceeds to offer him pot, and makes a feeble effort at seduction. The central male lead, Teddy, is a troubled (aren’t they all troubled? doesn’t that seem to be the plot structure and theme function?) teen with a friend Fred who keeps making destructive antisocial suggestions that somehow seem attractive; Teddy follows along, but with a quizzical expression that always fails to give full allegiance. Eventually he is arrested for one of their escapades and does community service in a children’s library.

Locke and The Rover offer intelligent and compelling performances by two actors (one British, the other Australian) somehow not fully familiar to American audiences: Tom Hardy and Guy Pearce. Hardy had offered an intensity and unpredictability in his earlier roles as Bain, the mouth-obscuring device villain of mysterious ethnicity and motivation in The Dark Knight Rises (2012), following an almost silent moody performance as a principled and indestructible moonshiner in Lawless. Pearce some readers will recognize as having played Edward VIII (George VI’s older brother, who abdicated in The King’s Speech, 2010), but also as having been long ago in L.A. Confidential (1997); in between he was a rapacious and epicene federal agent allied against Tom Hardy in Lawless (2012) as well as the central memory-loss character in Memento.

Neither actor is a your typical widescreen movie idol, a la Harrison Ford or Brad Pitt. There’s an element of tension or painful difference in each, and these two new films highlight this. Locke (2013, directed by Steven Knight) offers us, like so many opaque and distinctive films, a non-explanatory title and a puzzle as its central character, Locke. In fact, this character is its theme and its plot, as we follow along with Locke, seemingly in real time, as he drives from a giant construction jobsite in Northern England to London along an M highway on a journey that supposedly will transform his life. That’s it, that’s the whole film. One character, supposedly one scene, but not quite a monologue, because he’s a construction executive on his expensive BMW car phone during the whole drive . He’s speaking with either his wife, his sons, his construction crew associate, his boss, or an executive from the Chicago-based firm, or a possible girlfriend pregnant and delivering painfully in a London hospital.

It’s either a bravura performance or a tour-de-force or a terribly ambitious mistake in filming and conception; unfortunately, I vote for the last because of the ways in which these decisions reduce the power and scope of film itself. But we do get to know Locke intimately (perhaps his surname and the film’s title are an allusion to the British rational philosopher John Locke or the single-minded attitude he displays in his drive). Locke decides spontaneously or impetuously to abandon a key job and risk his marital life to be by the side of a woman he had a brief coupling with nine months ago.

The portrait that emerges of the man is revealed by his careful responses in phone conversations in that he always seems to be telling the truth and evading emotional ranting: the pregnant woman asks him to tell her he loves her; it would be simple to say so, to comfort her, as he clearly wants to do, but he simply says, in effect, how would he know, he only spent a night with her, a non-commital answer. He is equally rational and deliberate and patient with members of his family and the gradually drunk subordinate who must supervise Europe’s “biggest concrete pour” over the next several hours. His other interlocutor is an imagined presence in the back seat of the BMW, his dead father who never acknowledged him when he was born. This is what used to be called dollar-book Freud; I don’t think it has become any more convincing or expensive in the years since and, to me, seems the weakest part of the film.

Though supposedly Locke is in a hurry to reach the side of the woman before she gives birth, we see in the windscreen of his car many other vehicles pass him on the superhighway. His radical decision is apparently not so forthright or certain. But in his conversation with others, he is certain, self-assured. He doesn’t seem to want to abandon his wife and sons, but she throws him out “on the phone,” as it were. He doesn’t want to abandon his job, and we see his expertise and determination in pouring concrete and in chasing down city councilmen and police officers to make sure it arrives on time. He is fired, but there is hardly any doubt he will find a new job. But this is hard to take for two hours nonstop. We want what movies generally give us, the intrusion of other characters, other sites, other complications. But Locke is unrelenting; Hardy plays well these determined and unrelenting characters.

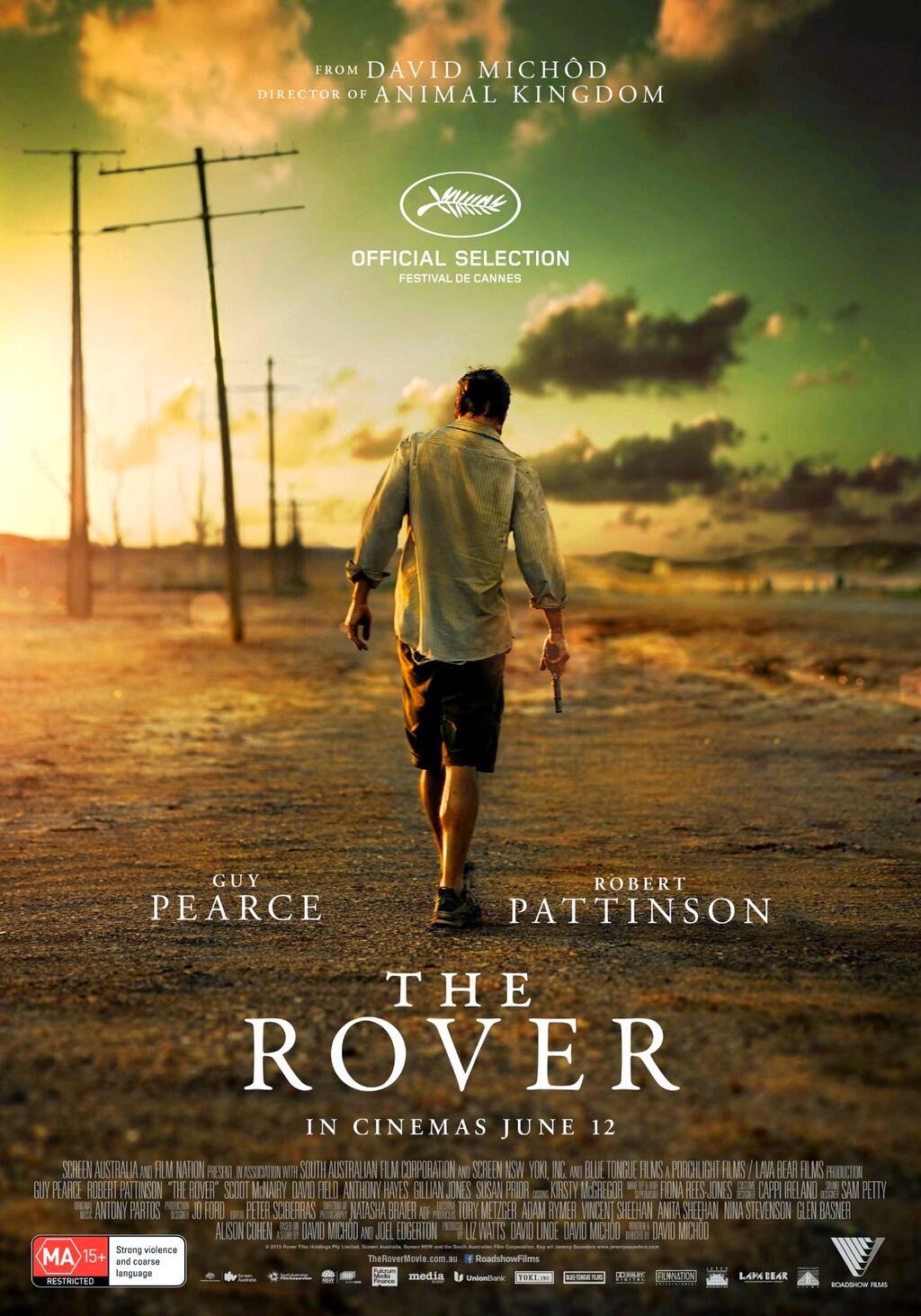

The Rover (2014, directed by David Michôd) is another portrait of a monomaniac, the unnamed character played by Pearce, but it is also the revelation of a far different world, a world that is so recurrently portrayed in films that, to me at least, it is hardly interesting: the world that is the end of worlds, the post-apocalyptic time of anarchic behavior. And the worlds these display are always dystopic and sadly predictable and uninspired – whether it’s The Road (2009) or Elysium (2013) or even Planet of the Apes (1968, 1974, 2001). Some catastrophe, nuclear or geopolitical or ecological, has made the world largely uninhabitable and groups of humans (or apes, in those eponymous films) roam and behave in unpredictable and vaguely threatening ways.

In The Rover we are told only that the landscape we first see, of lonely homes and trailers and autos roaming, is “ten years after the collapse,” and, given the explicit refusal of many vendors to accept Australian currency, Australia. (America apparently is still stable or unharmed, because vendors will accept American dollars.) In the trailer these scenes are subtitled with the powerful opening lines from Yeats’s “The Second Coming” – “things fall apart…the centre cannot hold” – depicting a terrifying anarchic and yet poetic world. The landscape is the barren iconic landscape, as several reviews have pointed out, of the older Westerns I mentioned at the beginning of this article: but it is a deeply fallen West, if so, and its heroic actions are all absurd; eventually, if we stay to the end, we think we understand the reasons for Eric’s extreme behavior.

Pearce seems aging, off-kilter, his face and shirt uncertain or tilted; and we know little of his origins or what he seeks: except that when someone steals his car, he pursues them relentlessly and ruthlessly, though he has at first no weapon. The film is primarily about the landscape he encounters, mostly of aging, oddly paired men, with few women, one a doctor, one an aging grandmother-like figure in a rocker who politely asks Eric his name and offers him an attractive young boy as Eric points a gun at her head. These isolated men live in slowly decaying suburban homes or trailers and cower or sleep in dark rooms, or offer to sell food, and occasionally other human beings for sex. But all is uncertain: What are the rules? What caused the collapse? The Rover, asked repeatedly, refuses to give his name.

There has been some kind of collapse that makes some men horde unappealing food and cower in rooms and steal cars and shoot at each other. At first there is apparently no center, no organization. Yet the outposts we see sell jerry-cans of petrol even if there are no gas stations. And later we are startled to see a long train moving through the barren landscape, even if it contains soldiers occasionally on flatcars manning machine guns. Eric is eventually apprehended by some other soldiers near an abandoned mine and taken to a base and told he will be sent to Sydney, but we don’t know for what crime or what fate awaits him. The mystery at the heart of this film, and its barren, unpredictably violent, tone are what make it distinctive.

from the mythical west to the dystopian future

By Jonathan Price

The films A Million Ways to Die in the West, Chef, Palo Alto, Locke, and The Rover represent ones I’ve seen within the last month, and they merit some attention, even if you decide not to see them. But each seems to represent a different genre, or a different tendency in filmmaking, and a different tendency of some creative people to move off in new directions, but most still remain disappointing in some way.

In A Million Ways to Die in the West (2014, directed by Seth MacFarlane), the title seems to encompass the plot; and it’s obviously a Western, but the Western, like the dying West, is a dying genre, only it’s been dying for a long time. The first American feature film was a Western, The Great Train Robbery (1903). At the very beginning of filmmaking when writers, cameramen, directors, and audiences were still trying to create, delineate, and appreciate this startling new development in technology, it was silent, only 10 minutes long, “based on a true story,” and in New Jersey, with its spindly birches – not an iconic Western landscape with mountains and deserts. This was some 30 years before the Western became an iconic, mythic form, almost a ritual or sacrament and a mainstay of film narratives for three decades. The West to which it had referred had begun to atrophy soon after the Civil War’s end in 1865 and was pretty much a dead issue by 1890, some ten years before its first cinematic version.

But one key element in the Western is nearly always nostalgia – loss and longing. Some of its other constituent narrative and visual elements, which you may recognize from your childhood and the following list, which are duly ticked off in A Million Ways to Die in the West: long rides across barren spaces on horseback, set against a backdrop of monoliths (often from Arizona’s Monument Valley, as if they were scenery dragged out at Western movie-making-time), climactic gunfights (this film has three), a race between a train and horses, sheepherders, Indians, the hero gets the girl. A Million Ways parodies all of these, deconstructing them but going far beyond the American revisionist Westerns of the late 1960s (think of The Wild Bunch, 1969, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, 1971, even Blazing Saddles, 1974) into superficial sarcasm and ultimately sophomoric humor – fart jokes and references to fellatio and anal intercourse supposedly replace plot, theme, and, sadly, entertainment.

The trouble with this brand of humor is that it appears to be thrown in to show how hip the film is, how it doesn’t believe any of the myths. Instead it is often irritating, or just juvenile or silly. But it does have an unusual performance by Charlize Theron as the gunslinger’s sympathetic (to the hero), yet bitter wife, and Theron has said she was dying to get the role. The film was written, directed by, and stars Seth MacFarlane. Its other noteworthy feature is a series of cameos by various actors, usually placed for their anachronistic value in deconstructing the Western itself – Jamie Foxx as Django in an antiracist killing tucked into the credits, Bill Maher in a comic bit, a figure from Back to the Future discovered in a garage, Wes Studi as Cochise.

Chef (2014, directed by Jon Favreau) is – guess what? – a movie about food and making it. The title suggests a documentary, but we get a quirky independent feature film about an innovative, talented chef trying to save his Los Angeles restaurant’s class without alienating his boss, the owner (Dustin Hoffman), for whom profits come first. The first third of the film is exciting, enthusiastic, with collages of the chef buying food, sampling techniques, preparing it, and delighting his staff and friends with samples – even seducing his much younger hostess, played by Scarlett Johansson, with a food preparation that subtly borders on the erotic, and makes us wish we there…to sample the food. He also has an intriguing relationship with his son and ex-wife (who, contrary to type in divorcee films, is totally supportive).

And then the film breaks down into renewed (supposedly) gourmet enthusiasm with a new project to purchase a very used food truck in Miami and drive it across country cooking Cuban sandwiches in key locales, such as New Orleans. This fails in two ways at once: the clientele may be enthusiastic, but apparently they are all tasting the two or three items of cuisine served by the truck – this doesn’t mesh with the chef’s gourmet enthusiasm and innovation; the city by city locations required by the geography of America (from Florida to California) present no development of theme, character, or even urban character; it’s as if we’re watching a boring reality show. And the film trails off in predictable ways.

Palo Alto (2013, directed by Gia Coppola) is an opaquely titled film that was (probably) shown in all of seven theaters across America. Supposedly set in Palo Alto, California (though it was shot in Southern California locales) and based on a collection of short stories with the eponymous title by James Franco, who also acts in a key role, the film is a series of coming-of-age vignettes about a predictably dysfunctional group of teens without genuine adult guidance. Despite the fact that Stanford is just around the corner (though in its own municipality) and that Palo Alto itself is in the center of Silicon Valley with several certified billionaires lining its city streets, there seems to be no interest in class, sociology, microchips, or even much sense of location. Palo Alto, Spanish for “tall stick” is supposedly derived from a stand of redwoods last seen two centuries ago; no one connected to the film seems to be concerned with this origin either. There are instead a lot of short sticks and immature characters around.

The only thematic given is the failure of father figures, including but not limited to the soccer coach/teacher at the local high school, played by Franco, who seduces his teen star and babysitter April, the sensitive figure in the film who, sadly and perhaps inevitably, is dismayed when she finds her seduction is part of a player-babysitter seduction succession. There are, surprisingly, few fathers to be found, though supposedly Silicon Valley is overpopulated by successful young males (compared to females). One father invites his son’s male friend in, proceeds to offer him pot, and makes a feeble effort at seduction. The central male lead, Teddy, is a troubled (aren’t they all troubled? doesn’t that seem to be the plot structure and theme function?) teen with a friend Fred who keeps making destructive antisocial suggestions that somehow seem attractive; Teddy follows along, but with a quizzical expression that always fails to give full allegiance. Eventually he is arrested for one of their escapades and does community service in a children’s library.

Locke and The Rover offer intelligent and compelling performances by two actors (one British, the other Australian) somehow not fully familiar to American audiences: Tom Hardy and Guy Pearce. Hardy had offered an intensity and unpredictability in his earlier roles as Bain, the mouth-obscuring device villain of mysterious ethnicity and motivation in The Dark Knight Rises (2012), following an almost silent moody performance as a principled and indestructible moonshiner in Lawless. Pearce some readers will recognize as having played Edward VIII (George VI’s older brother, who abdicated in The King’s Speech, 2010), but also as having been long ago in L.A. Confidential (1997); in between he was a rapacious and epicene federal agent allied against Tom Hardy in Lawless (2012) as well as the central memory-loss character in Memento.

Neither actor is a your typical widescreen movie idol, a la Harrison Ford or Brad Pitt. There’s an element of tension or painful difference in each, and these two new films highlight this. Locke (2013, directed by Steven Knight) offers us, like so many opaque and distinctive films, a non-explanatory title and a puzzle as its central character, Locke. In fact, this character is its theme and its plot, as we follow along with Locke, seemingly in real time, as he drives from a giant construction jobsite in Northern England to London along an M highway on a journey that supposedly will transform his life. That’s it, that’s the whole film. One character, supposedly one scene, but not quite a monologue, because he’s a construction executive on his expensive BMW car phone during the whole drive . He’s speaking with either his wife, his sons, his construction crew associate, his boss, or an executive from the Chicago-based firm, or a possible girlfriend pregnant and delivering painfully in a London hospital.

It’s either a bravura performance or a tour-de-force or a terribly ambitious mistake in filming and conception; unfortunately, I vote for the last because of the ways in which these decisions reduce the power and scope of film itself. But we do get to know Locke intimately (perhaps his surname and the film’s title are an allusion to the British rational philosopher John Locke or the single-minded attitude he displays in his drive). Locke decides spontaneously or impetuously to abandon a key job and risk his marital life to be by the side of a woman he had a brief coupling with nine months ago.

The portrait that emerges of the man is revealed by his careful responses in phone conversations in that he always seems to be telling the truth and evading emotional ranting: the pregnant woman asks him to tell her he loves her; it would be simple to say so, to comfort her, as he clearly wants to do, but he simply says, in effect, how would he know, he only spent a night with her, a non-commital answer. He is equally rational and deliberate and patient with members of his family and the gradually drunk subordinate who must supervise Europe’s “biggest concrete pour” over the next several hours. His other interlocutor is an imagined presence in the back seat of the BMW, his dead father who never acknowledged him when he was born. This is what used to be called dollar-book Freud; I don’t think it has become any more convincing or expensive in the years since and, to me, seems the weakest part of the film.

Though supposedly Locke is in a hurry to reach the side of the woman before she gives birth, we see in the windscreen of his car many other vehicles pass him on the superhighway. His radical decision is apparently not so forthright or certain. But in his conversation with others, he is certain, self-assured. He doesn’t seem to want to abandon his wife and sons, but she throws him out “on the phone,” as it were. He doesn’t want to abandon his job, and we see his expertise and determination in pouring concrete and in chasing down city councilmen and police officers to make sure it arrives on time. He is fired, but there is hardly any doubt he will find a new job. But this is hard to take for two hours nonstop. We want what movies generally give us, the intrusion of other characters, other sites, other complications. But Locke is unrelenting; Hardy plays well these determined and unrelenting characters.

The Rover (2014, directed by David Michôd) is another portrait of a monomaniac, the unnamed character played by Pearce, but it is also the revelation of a far different world, a world that is so recurrently portrayed in films that, to me at least, it is hardly interesting: the world that is the end of worlds, the post-apocalyptic time of anarchic behavior. And the worlds these display are always dystopic and sadly predictable and uninspired – whether it’s The Road (2009) or Elysium (2013) or even Planet of the Apes (1968, 1974, 2001). Some catastrophe, nuclear or geopolitical or ecological, has made the world largely uninhabitable and groups of humans (or apes, in those eponymous films) roam and behave in unpredictable and vaguely threatening ways.

In The Rover we are told only that the landscape we first see, of lonely homes and trailers and autos roaming, is “ten years after the collapse,” and, given the explicit refusal of many vendors to accept Australian currency, Australia. (America apparently is still stable or unharmed, because vendors will accept American dollars.) In the trailer these scenes are subtitled with the powerful opening lines from Yeats’s “The Second Coming” – “things fall apart…the centre cannot hold” – depicting a terrifying anarchic and yet poetic world. The landscape is the barren iconic landscape, as several reviews have pointed out, of the older Westerns I mentioned at the beginning of this article: but it is a deeply fallen West, if so, and its heroic actions are all absurd; eventually, if we stay to the end, we think we understand the reasons for Eric’s extreme behavior.

Pearce seems aging, off-kilter, his face and shirt uncertain or tilted; and we know little of his origins or what he seeks: except that when someone steals his car, he pursues them relentlessly and ruthlessly, though he has at first no weapon. The film is primarily about the landscape he encounters, mostly of aging, oddly paired men, with few women, one a doctor, one an aging grandmother-like figure in a rocker who politely asks Eric his name and offers him an attractive young boy as Eric points a gun at her head. These isolated men live in slowly decaying suburban homes or trailers and cower or sleep in dark rooms, or offer to sell food, and occasionally other human beings for sex. But all is uncertain: What are the rules? What caused the collapse? The Rover, asked repeatedly, refuses to give his name.

There has been some kind of collapse that makes some men horde unappealing food and cower in rooms and steal cars and shoot at each other. At first there is apparently no center, no organization. Yet the outposts we see sell jerry-cans of petrol even if there are no gas stations. And later we are startled to see a long train moving through the barren landscape, even if it contains soldiers occasionally on flatcars manning machine guns. Eric is eventually apprehended by some other soldiers near an abandoned mine and taken to a base and told he will be sent to Sydney, but we don’t know for what crime or what fate awaits him. The mystery at the heart of this film, and its barren, unpredictably violent, tone are what make it distinctive.

| Copyright © 2014 by Jonathan Price |

+2+(120).jpg)

Kinda discouraging, is it just a bad year for movies? Even Andrew O'Hehir in Salon seems to find politics more compelling as a subject. Makes me want to stay home and breakout the DVDs. Seven Samurai? or Bad Day at Black Rock? maybe Porco Rosso?

ReplyDeleteJonathan, as I told you in an email, even though I wouldn't want to see any one of these films, I enjoyed learning the reasons why. You indicated that you'd go see at least two of them again. Which two? I might give them a try. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteJonathan relays by way of email:

DeleteChef and The Rover.

Thanks for asking, sorry for the seeming downbeat consensus in the five reviews.

I saw Chef and thought it was wonderful, the sleeper of the summer. I have not seen any of the others.

ReplyDeleteIt was one I could see again. Just a cute movie makes you laugh and a enjoyable afternoon or evening out....you will be hungry for some good Mexican food....

DeleteInteresting. I just watched Chef but have not yet seen the others.

ReplyDelete