It’s an art

By Moristotle

[Originally published on June 5, 2014]

A passage in John E. Smith’s study of The Spirit of American Philosophy recently brought me full-stop. It was like the birth of Minerva from my own skull.

The passage was in Chapter IV, on the philosophy of John Dewey, and it was about Dewey’s conception of art. It provided a formula or metaphor for me to express my own personal sense of the holy or sacred.

Professor Smith wrote that a trend among twentieth-century thinkers was that

And it’s not just my experience that is valuable. All life on Earth grew out of Earth. I value and respect the experience of others, and include in “others” not only humans but also non-human animals. (They are our relatives, after all.) On this core value is founded my sense of morality, of what is right. It is wrong, for example, to treat a pet, or a farm or ranch animal – or a wild animal – inhumanely, or to end its life unnecessarily. Those animals, too, are in the same situation. For them, too, this is it, this is all there is. Each one passes this way once; each animal is here and gone; it, too, deserves to have and hold its life.

My disbelief in God – and of the supernatural in general – has not left me unreligious in this sense.

One failing of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) is that they don’t champion animal rights. They condone the subjugation of animals in general (not to mention out-group humans in particular, whom, for example, they may kill for supposed offenses against their God or His chosen people; whom they may enslave; whose wives they may steal for themselves; whom they may even offer up for sacrifice if they’re feeling desperately in need of salvation)....

That is, for these religions, not all experience is valuable for its own sake – certainly not the experience of non-human animals, whom people may sacrifice for their various rituals or propitiations, and even eat with no qualm whatsoever.

A second flaw is that these religions devalue experience that doesn’t occur on the “holy days.” They implicitly demote days that aren’t sabbaths (or Saint’s days, or other religious holidays) to a lesser status. You’re to observe “the Lord’s day” by doing no work, but on your days for doing as you please you can work. The subtext seems to be that you are not to think of “your” days as holy or sacred.

The result seems to be that people live from holiday to holiday, hoping for something transcendent and liberating that never quite comes, for it has been overlooked on all the little, ordinary days, as people have failed to experience and value their lives in themselves, failed to appreciate the sacred in all their ordinary, daily moments. They haven’t learned to recognize it because it has been demoted and neglected. The Abrahamic religions have distracted people away from the daily sacred and corrupted their ordinary experience – corrupted their lives – profoundly.

I mention those deficiencies because they are pertinent to the art of treating experience (everyone’s and everyday’s) as valuable for its own sake – that is, as sacred. But those faults didn’t arise in a vacuum; they follow from other defects of the world’s Big Three theistic religions:

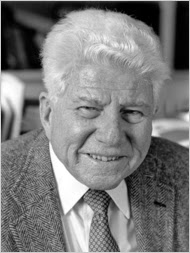

[Note: John E. Smith was the Chairman of the Philosophy Department at Yale when I was an undergraduate there, and my scholarship job for three years was to be his "bursary student." I supported his office staff, made copies, did some research, some typing, that sort of thing. I noted his death in December 2009 ("Death, too, is what happens").]

By Moristotle

[Originally published on June 5, 2014]

A passage in John E. Smith’s study of The Spirit of American Philosophy recently brought me full-stop. It was like the birth of Minerva from my own skull.

The passage was in Chapter IV, on the philosophy of John Dewey, and it was about Dewey’s conception of art. It provided a formula or metaphor for me to express my own personal sense of the holy or sacred.

Professor Smith wrote that a trend among twentieth-century thinkers was that

Religion has fallen on evil days, the great moral traditions of Western civilization have been brought into question; science, progress, and the possibilities of history have been made to take their place. But for many this has not been enough. Is there, they have asked, no source of meaning for life which takes us beyond the struggle for existence? Is the whole of life to be summed up in the effort to master ourselves and our surroundings?...We want to go beyond organism and environment, beyond the push and pull of social and political life, to some ideal fulfillment that is more lasting than successful manipulation of things....This passage reminded me that my own, personal view of the sacredness of experience may essentially be an aesthetic view, especially in view of the fact that I have posted a number of “art pieces” in this column [Thor’s Day]. For example, “Perceiving beauty,” “Animal spirits,” “The sense of life...is life,” “Contemplative estheticism: From The Elegance of the Hedgehog.” I consider it a sacred art to live in a way that values life and respects one’s own and others’ experience for its own sake. I accept as self-evident that experience must be valuable for its own sake, for this is it, this is all there is. We pass this way once. Here and gone. We need to cherish it.

...Art as expression....What Dewey called the museum conception of art is to be rejected...it isolates art from experience...and severs the connection between artistic production and ordinary events of aesthetic interest by setting it up on a pedestal. Dewey argued instead for an understanding of art which sees it as a direct development stemming from aesthetic perception; art results from experience and, in a certain sense, is experience. It is experience in that heightened sense in which experience becomes valuable for its own sake. [emphasis mine; pp. 158-9 of the revised edition, 1982]

And it’s not just my experience that is valuable. All life on Earth grew out of Earth. I value and respect the experience of others, and include in “others” not only humans but also non-human animals. (They are our relatives, after all.) On this core value is founded my sense of morality, of what is right. It is wrong, for example, to treat a pet, or a farm or ranch animal – or a wild animal – inhumanely, or to end its life unnecessarily. Those animals, too, are in the same situation. For them, too, this is it, this is all there is. Each one passes this way once; each animal is here and gone; it, too, deserves to have and hold its life.

My disbelief in God – and of the supernatural in general – has not left me unreligious in this sense.

One failing of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) is that they don’t champion animal rights. They condone the subjugation of animals in general (not to mention out-group humans in particular, whom, for example, they may kill for supposed offenses against their God or His chosen people; whom they may enslave; whose wives they may steal for themselves; whom they may even offer up for sacrifice if they’re feeling desperately in need of salvation)....

That is, for these religions, not all experience is valuable for its own sake – certainly not the experience of non-human animals, whom people may sacrifice for their various rituals or propitiations, and even eat with no qualm whatsoever.

A second flaw is that these religions devalue experience that doesn’t occur on the “holy days.” They implicitly demote days that aren’t sabbaths (or Saint’s days, or other religious holidays) to a lesser status. You’re to observe “the Lord’s day” by doing no work, but on your days for doing as you please you can work. The subtext seems to be that you are not to think of “your” days as holy or sacred.

The result seems to be that people live from holiday to holiday, hoping for something transcendent and liberating that never quite comes, for it has been overlooked on all the little, ordinary days, as people have failed to experience and value their lives in themselves, failed to appreciate the sacred in all their ordinary, daily moments. They haven’t learned to recognize it because it has been demoted and neglected. The Abrahamic religions have distracted people away from the daily sacred and corrupted their ordinary experience – corrupted their lives – profoundly.

I mention those deficiencies because they are pertinent to the art of treating experience (everyone’s and everyday’s) as valuable for its own sake – that is, as sacred. But those faults didn’t arise in a vacuum; they follow from other defects of the world’s Big Three theistic religions:

- The Abrahamic religions are founded on fantasies, day-dreams, hallucinations, delusions, fanciful notions, manic visions, wishful thoughts, magical thinking, received myths...that simply aren’t true – articulate burning bushes, talking snakes, waging spirits, parting red seas, immaculate conceptions, bodily resurrections, apocalyptic returns, final judgments, heaven, hell, 70-some-odd virgins waiting upstairs to spread their legs for sexually repressed jihadists....

- They promote or condone as moral the treatment of other people and of animals that is actually immoral – human and other-animal sacrifice (the crucifixion of Jesus was an act of human sacrifice, after all – at least as framed by later Christian writers, who were intent on founding a religion); subjugation of women; "honor" killing of daughters who have sex out of wedlock, consensually or otherwise; outing of gays (contemporary American Christians and Muslims in Africa, Europe, and Asia are warring on gays everyday); covering up sexual abuse of children by clerics (it’s still going on in the Roman Catholic Church); accumulation of disproportionate wealth by “chosen” or “elect” people (a popular rallying point for televangelists and mega-business-churches in the United States); rationalization of crimes for which they can be forgiven because “the Son of God died for them,” or because they confess, “atone,” and do the prescribed number of penances....

- They subjugate followers through fear and intimidation – warnings that if people don’t believe certain things they will not go to heaven, or that if they do certain things they will surely burn in hell; the requirement that in order to be pure they do the prescribed number of prayers per day in the prescribed manner and facing in the prescribed direction; threats of stoning or beheading or exile if they don’t believe the officially prescribed things; literal judicial executions for apostasy (as Leonard Pitts reports of a current case in Khartoum, in his column “Faith cannot be coerced,” in which he writes, “Meriam Yehya Ibrahim...stands convicted of apostasy. She renounced Islam and became a Christian...Converting from Islam is against the law....”)....

- They dull the minds of many of their followers with dogmatic poppycock that leaves them unreachable through rationality and science – the earth (the whole universe?) is just over 6,000 years old; Adam & Eve were created in human form and are the parents of mankind; supernatural spirits can intervene willy-nilly in the workings of the material universe, and can either acquiesce in, ignore, or reject the prayers of the faithful (it’s the faithful’s option to decide which alternative his or her God chose, of course)....

[Note: John E. Smith was the Chairman of the Philosophy Department at Yale when I was an undergraduate there, and my scholarship job for three years was to be his "bursary student." I supported his office staff, made copies, did some research, some typing, that sort of thing. I noted his death in December 2009 ("Death, too, is what happens").]

| Copyright © 2018 by Moristotle |

.jpg)

Very interesting piece, it went well with my coffee. I've known a few free thinkers in my life who would whole heartily agree with you. While I've known others who would be willing to see such thinkers burned. All this for the answer to the great unknown which can be answered only by dying.

ReplyDeleteEd, if there is nothing to be experienced after death, then I don’t believe that anyone is going to be getting that answer. What am I missing?

DeleteThe idea of heightened experience or the “daily sacred” seems compatible with Heidegger’s concept, as you’ve talked about of being present - being with others and being FOR others. The trouble is how personal beliefs thwart the level of acceptance needed to just be content that others, others with other beliefs, are having their own experiences. Ed, I think you’ve hit on that by identifying two different camps - the reaction of each camp to Moristotle’s way of thinking would be diametrically opposed precisely because each camp is doing the same kind of excluding or devaluing of the other camp’s thinking and experience. We seem to have moved since the Enlightenment far away from the integrating, inclusive thinking that could allow us to truly value all experience. How to embrace other people’s right to believe and experience in a way one doesn’t believe in oneself, when the “rational” impulse is to critique those other beliefs in defense of one’s own? It’s like trying to build a bridge by creating a chasm.

ReplyDeleteI fear the problem is that there is no debate any longer. One side is using the power of the vote to do away with debate and just change the law to refract their view point or erase the ours point of view.

DeleteI’ll have to re-read my essay to see whether I can agree that I was/am devaluing the experience of people whose understanding is “diametrically opposed” to mine. I take it that is what is being suggested?

DeleteBut right now I’m resting outside in a shade a few feet away from where I have been taking out the third of three thick plants my wife wants gone. Still got two stumps to reduce.

Having just re-read my essay, it seems possible that my critique of “flaws” in the Abrahamic religions might be interpreted as a rejection of others’ “right to believe and experience in [their own way]” [emphasis mine]. If it were interpreted that way, then I must say that that isn’t (and wasn’t) my position. We all have a right to our ways of living (so long as they don’t harm others). And we all have a right to make moral judgments, according to our respective sense of what is right and what is wrong. I do not refrain from using the word “immoral” in my essay.

ReplyDeleteThe “worst” that I was and am doing is to suggest that experience that grows out of, or is founded on, what I regard as “flawed” beliefs could be new and different and – even from the point of view of those believers, if reformed – deeper, richer, more inclusive than their old experience.

I hoped to be shining a torchlight. If clumsiness on my part caused the torch to fall on someone’s head, that is to be regretted. The most constructive remedy for that is to pick the torch up and continue shining it.

Afterthought. Maybe beliefs don’t so much “grow out of,” aren’t so much “founded on” beliefs as the other way around? Maybe I was wring about that....Maybe the torchlight needs to be a heater or a fan?

Delete