With Updike, the subject hardly matters. Who was it who said that Updike never wrote an uninteresting sentence?

The orange of the Gulf sign at the all-night gas station two blocks away is the only emphatic touch of color in the pre-dawn vista. Here and there in the neighborhood a wan, low-voltage night light warms the window of a child's room or a stair landing. In the semi-darkness, under a polished dome of darkness weakened by the climbing rot of city glow, the fore-shortened angles of roof lines, shingles, and sidings recedes to infinity. [at approximately the 55-minute point of a 10-hour, 37-minute reading](How could my Yale roommate Jim Carney possibly have been sincere in comparing my own collegiate letter writing to Updike's?)

When he wrote Terrorist, Updike was about Krapp's age, and mine—a few years older. And high school guidance counselor Jack Levy, who witnessed the scene depicted above, was only a year ahead of me in high school:

Prize student at Central High, Class of '59, before it felt so much like a prison and you could still study and take pride in the praise of the teachers.Yes, those were the days.

Jack has been lying in bed reflecting on his life:

It was like tuning the violin he used to play in his boyhood. "Another Heifetz, another Isaac Stern." Is that what his parents had hoped for?But now,

He disappointed them, a segment of misery where his own and the world's coincided. His parents grieved. He had defiantly told them he was quitting lessons; the life in books and on the streets meant more to him. He was eleven, maybe twelve, to take such a stand, and never picked up the violin again, though sometimes, hearing on the car radio a snatch of Beethoven or a Mozart concerto or Dvořák's gypsy music that he had once practiced in a student arrangement, Jack is surprised to feel the fingering trying to live again in his left hand, twitching on the steering wheel like a dying fish. [at approximately the 44-minute point]

He lies exposed, as to a sickening blast of radioactivity, to an awareness of his life as a needless blot, a botch, a prolonged blunder imposed upon the otherwise immaculate surface of this ungodly hour.It's the world in which American-born Muslim teenager Ahmad Ashmawy Mulloy will be drawn (implausibly? see below) into a terrorist plot against "infidels"....

In the world's dark forest he had missed the right path. But was there any right path, or was being alive in itself the mistake?

In the stripped-down history that he used to purvey to students who had trouble believing that the world didn't begin with their births and the proliferation of computer games, even the greatest men came to nothing, to a grave, their visions unfulfilled—Charlemagne, Charles the Fifth, Napoleon, the unspeakable but considerably successful and still, at least in the Arab world, admired Adolf Hitler. History is a machine perpetually grinding mankind to dust.

Jack Levy's guidance counseling replays in his head as a cacophony of miscommunication. He sees himself as a pathetic elderly figure on a shore, shouting out to a flotilla of the young as they slide into the fatal morass of the world, its dwindling resources, its disappearing freedoms, its merciless advertisements geared to a preposterous popular culture of eternal music and beer and impossibly fit and thin young females. [at approximately the 49-minute point]

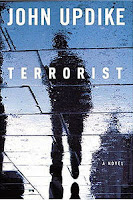

I'm on Orange Alert, however. Christopher Hitchens sent Terrorist "windmilling across the room in a spasm of boredom and annoyance," he wrote in his review in The Atlantic (June 2006, "John Updike, Part One: No Way") [p. 101 of Arguably]. He judged it "one of the worst pieces of writing from any grown-up source since the events he has so unwisely tried to draw upon" and judged Updike as "someone who has been keeping up with the 'Inside Radical Islam' features in something like Newsweek. [p. 103]

Hitchens did allow, though, in his "Farewell to a Much-Misunderstood Man" (Slate, February 2, 2009), that "Perhaps Updike [1932-2009] was too ill by then. And something seemed to have gone wrong with his confidence toward the end. His 2006 novel, Terrorist, was a failure of nerve...."

[Follow-up]

No comments:

Post a Comment