Part 1 of 3

By Bob Boldt

No matter how good or bad things got, Mother could never shake her unspoken belief that things could always get worse. I had my own version, which was, things could suddenly go bad in a nano-second, or be rescued in the next.

When I was living my prior, typical, white-boy, college-boy, frat-boy life, my roommate was the smartest guy in our fraternity and likely in his whole class of ’58, Wabash College, Crawfordsville, Indiana. I had built an Art Deco bookcase. Our room still bore the faint tint of my final coat of varnish applied yesterday. I’d wait till after Homecoming week to fish my library out of the closet and fill my creation. My roommate was Bill, Bill Fisher. He ascended pretty high up in the “Intelligence community.” Community, like that’s so down-home sounding, like spooks shooting the shit across the back fence.

His parents went positively agog over my bookcase, the natural wood finish, the sleek aluminum posts that seemed to effortlessly support the shelf structure. It was a decent looking Art Deco homage, nothing more. Bill’s dad, an overweight, white-haired gentleman who looked like he’d been cast off a Monopoly board, was bemoaning what a bad carpenter his son had been in shop class in high school. Like it was some kind of supreme test of manhood to make a stupid bird house or something. I hated the beaten expression on my friend’s face as his dad was berating his genius kid over the head with my dumb bookcase. I felt sorry for Bill, who was good enough for Phi Beta Kappa, but not for his own fucking parents.

We were among the Greeks, already our own kind of social elite. The War and the GI Bill produced the greatest upward class mobility in history. It meant that the kids of the newly arrived affluent class were about to take a big bite of well fought and won American pie. My dad started out as a sign painter, served in the Navy in World War Two, and graduated technical school. At Wabash. I got to see both the cream of the economic elite and kids like me from families who came up the hard way. I always found the carpenter, the lineman, the plumber parents far more loving and prouder of their kids than the wealthy, upper crust parents. Bill’s dad’s treatment of his son, his lack of even minimal affection, haunted him like nothing else. All those brains and such a tormented soul. It’s almost enough to make me pity the son of a psychopath who went on to become president. Hopefully the guys and gals my old pal Bill trained are just destroying third-world countries now, not leading insurrections in-country.

My draft situation was enviable, situated as I was in the trough between the two big wars after World War Two. I found my own way to dodge my service to help my country in its effort “to die for me.” Everyone I knew was finding ways, creative ways, of draft dodging, not just Arlo Guthrie. I remember seeing the captain of our Senior year football team bending over and spreading ’em in front of the Sergeant. He was looking all scared shitless. He looked to me like an ironic, bent Adonis by the glass block light on the third floor of the Chicago Draft Examination Station. He was killed in a Huey over Da Nang. There’s a picture of him in uniform next to the Varsity team trophy he earned in 1954.

The gods must have been determined to have the last laugh because, I had no sooner loaded the last volume of Proust to the top shelf when all the nails I had used to support the shelves on the sleek aluminum columns failed simultaneously, catapulting all the books in a great cascade onto the floor. Later autopsy determined it was a controlled demolition. All I could do was laugh. I wish Bill’s dad had witnessed the splendiferous catastrophe.

1962 was my second and final semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After many weekend sleepovers, Regula moved in with me lock, stock, and easel. She and three 50-lb litho stones. We had all just been through the Cuban Missile Crisis. I was only eight years old when the Second World War ended. My earliest memories in my life were of everyone I knew frightened we might lose that war.

These earliest, almost primal, repressed fears were very much on my mind when I stepped out onto Monroe Street after class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that afternoon. South of the Second City, along the coast of Lake Michigan, were the massive steel foundries and milling plants of Gary, Indiana. That had to be one of the prime targets for a Russian missile, as well as Chicago, a population and commercial center. A perfect two-fer!

On the first Friday of the crisis, I walked out of class onto Monroe Street. An afternoon coolness emanated off Lake Michigan all along Grant Park a block away. As I moved west toward Michigan Avenue and the Wabash Avenue elevated ride home, I noticed city workmen reconstructing a damaged piece of curbing. The forms had been set. They were using wide shovels to scoop wet cement from a mixer carefully shoveling it into each allotted location. I paused to watch a moment. It wasn’t just the pungent, damp concrete smell that arrested my attention that afternoon. It was the idea that we could be all incinerated like in the forbidden news photographs of shadows from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I thought about how the concrete would boil away past charred plywood and bone all obeying the laws of nature and nuclear physics. I looked and closed my eyes and imagined what I might see after that lethal blast. A couple of burned women from Hiroshima flashed in my head, then nothing. I told Regula about my vision. We smoked some weed, made love, and slept to the punctuation of the Armitage Avenue CTA bus hitting that damn pothole outside our door every 20 minutes.

It would be Halloween on Wednesday. Funny how, at times of near death, personal, or social, Americans seem to lose interest in the skulls and trappings when real skulls are at stake. When metaphors dissolve the mask, reality no longer seems so funny.

“Scrambled or easy over?” came a question from the kitchen. It was an interesting neighborhood our storefront studio was in. Its dangers were few but sudden. I only experienced three beatings during my tenure in the 43rd Ward. When you are a twenty-something, thinking you are immortal, gives one a delightfully false sense of security. Besides, we were artists so enthralled with art and each other, material things beyond paint and canvass seemed irrelevancies. The occasional need for practical action, when it arose, was handled. We were not stupid. It was a tough neighborhood sitting like some tribal fault-line in the Middle East War. Our neighborhood was Ground Zero in the city’s advancing push into gentrification.

“Is this a Halloween type party?” Bending over the open refrigerator light her waist-long brunette hair cascaded off her bare shoulder like a transparent curtain framing the silhouette profile of her face. Regula Zeller was born in Switzerland, but her physiognomy suggested distinct Asian traces: high cheek bones, full lips and deep looking brown eyes. Karl Jung was her great, great, grand uncle.

“All Kim said was it would definitely not be like anything else. It’s going to be at El Sabarum, you know that shop up on Halsted.”

“They call it a bottega. That’s where I bought our candles and sandalwood incense. A lady named Isobel owns it. She doesn’t speak much English. Her son helps her run it.”

It was more than a bottega. At least the time I stopped by on my way to dancer, Kim On Wong’s. El Sabaram as the establishment was christened, occupied one of the many storefronts that lined Halstead Street, the longest street in America someone said. It stretched from the Bohemian Villages on the South Side all the way to Evanston.

I certainly was up for a distraction, and it was distraction on my mind that evening. We met at Kim’s studio, a block away and walked cross Halsted Street at exactly quarter to ten, October thirty-first, Wednesday to be exact. The night had an electric quality not just born out of anticipation. The mercury vapor blue of the streetlights glinted off the car chrome as a light rain began making funhouse mirrors of asphalt and windshields. It was so refreshing we didn’t even think to use our umbrellas. We padded along, Regula in her leather sandals, me in my tennis shoes, and Kim clopping along in his Geta sandals. In his Japanese monk’s robe and conical hat he looked in the misty atmosphere of North Halstead Street Chicago like a character from a Hokusai painting.

By Bob Boldt

No matter how good or bad things got, Mother could never shake her unspoken belief that things could always get worse. I had my own version, which was, things could suddenly go bad in a nano-second, or be rescued in the next.

|

| Everything can change in a nanosecond |

.jpg) |

| Me the photojournalist in action (Chicago, June 1968) |

.jpg) |

| Me in color (Chicago, June 1968) |

His parents went positively agog over my bookcase, the natural wood finish, the sleek aluminum posts that seemed to effortlessly support the shelf structure. It was a decent looking Art Deco homage, nothing more. Bill’s dad, an overweight, white-haired gentleman who looked like he’d been cast off a Monopoly board, was bemoaning what a bad carpenter his son had been in shop class in high school. Like it was some kind of supreme test of manhood to make a stupid bird house or something. I hated the beaten expression on my friend’s face as his dad was berating his genius kid over the head with my dumb bookcase. I felt sorry for Bill, who was good enough for Phi Beta Kappa, but not for his own fucking parents.

|

| Ahoy! |

|

| Tick tock said the clock |

The gods must have been determined to have the last laugh because, I had no sooner loaded the last volume of Proust to the top shelf when all the nails I had used to support the shelves on the sleek aluminum columns failed simultaneously, catapulting all the books in a great cascade onto the floor. Later autopsy determined it was a controlled demolition. All I could do was laugh. I wish Bill’s dad had witnessed the splendiferous catastrophe.

|

| By Lake Michigan’s shore (1964) |

|

| Me the artist in my studio |

Sinner what will you do?WFMT, Chicago’s Fine Arts FM radio-for-high-brows station played mostly classical music but also gave voice or ear to lovers of jazz, blues, country, and folk. It was a station you would expect lovers from the School of the Art Institute to awaken to every morning. For the duration of the Missile Crisis, every morning and every sign-out, they played the Gospel classic excerpted above out onto their airwaves. No one knew and everyone feared what could happen that day.

Sinner what will you do?

Sinner what will you do when the stars begin to fall?

You’ll weep for the rocks and mountains

You’ll weep for the rocks and mountains

When the stars begin to fall.

|

| Monroe Street Bridge |

|

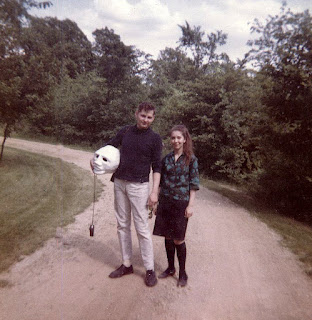

| Me and Regula 0n location |

“Scrambled or easy over?” came a question from the kitchen. It was an interesting neighborhood our storefront studio was in. Its dangers were few but sudden. I only experienced three beatings during my tenure in the 43rd Ward. When you are a twenty-something, thinking you are immortal, gives one a delightfully false sense of security. Besides, we were artists so enthralled with art and each other, material things beyond paint and canvass seemed irrelevancies. The occasional need for practical action, when it arose, was handled. We were not stupid. It was a tough neighborhood sitting like some tribal fault-line in the Middle East War. Our neighborhood was Ground Zero in the city’s advancing push into gentrification.

|

| With Regula, every day was Halloween! |

“All Kim said was it would definitely not be like anything else. It’s going to be at El Sabarum, you know that shop up on Halsted.”

“They call it a bottega. That’s where I bought our candles and sandalwood incense. A lady named Isobel owns it. She doesn’t speak much English. Her son helps her run it.”

It was more than a bottega. At least the time I stopped by on my way to dancer, Kim On Wong’s. El Sabaram as the establishment was christened, occupied one of the many storefronts that lined Halstead Street, the longest street in America someone said. It stretched from the Bohemian Villages on the South Side all the way to Evanston.

I certainly was up for a distraction, and it was distraction on my mind that evening. We met at Kim’s studio, a block away and walked cross Halsted Street at exactly quarter to ten, October thirty-first, Wednesday to be exact. The night had an electric quality not just born out of anticipation. The mercury vapor blue of the streetlights glinted off the car chrome as a light rain began making funhouse mirrors of asphalt and windshields. It was so refreshing we didn’t even think to use our umbrellas. We padded along, Regula in her leather sandals, me in my tennis shoes, and Kim clopping along in his Geta sandals. In his Japanese monk’s robe and conical hat he looked in the misty atmosphere of North Halstead Street Chicago like a character from a Hokusai painting.

| Copyright © 2022 by Bob Boldt |

Bob, I think your story with photos and (later) videos (and my arrangement of the latter here and there in the former), turned out rather well. What a life!

ReplyDeleteThanks for speeding my comeback to these screens. I have several other similar reminiscences I'm working on.

ReplyDeleteYou are most welcome, an honor to have you! I’m looking forward to further reminiscences. I hope I’ll be up to helping you publish your eventual book….

DeleteI knew this would be good. Can't wait for more.

ReplyDeleteSome of your best writing --ever! Thanks. And the photos you selected to go with it? Wow!

ReplyDeleteThanks Roger and Michael, and of course Moristotle!

ReplyDelete