It's an art

By Morris Dean

A passage in John E. Smith's study of The Spirit of American Philosophy recently brought me full-stop. It was like the birth of Minerva from my own skull.

The passage was in Chapter IV, on the philosophy of John Dewey, and it was about Dewey's conception of art. It provided a formula or metaphor for me to express my own personal sense of the holy or sacred.

Professor Smith wrote that a trend among twentieth-century thinkers was that

And it's not just my experience that is valuable. All life on Earth grew out of Earth. I value and respect the experience of others, and include in "others" not only humans but also non-human animals. (They are our relatives, after all.) On this core value is founded my sense of morality, of what is right. It is wrong, for example, to treat a pet, or a farm or ranch animal – or a wild animal – inhumanely, or to end its life unnecessarily. Those animals, too, are in the same situation. For them, too, this is it, this is all there is. Each one passes this way once; each animal is here and gone; it, too, deserves to have and hold its life.

My disbelief in God – and of the supernatural in general – has not left me unreligious in this sense.

One failing of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) is that they don't champion animal rights. They condone the subjugation of animals in general (not to mention out-group humans in particular, whom, for example, they may kill for supposed offenses against their God or His chosen people; whom they may enslave; whose wives they may steal for themselves; whom they may even offer up for sacrifice if they're feeling desperately in need of salvation)....

That is, for these religions, not all experience is valuable for its own sake – certainly not the experience of non-human animals, whom people may sacrifice for their various rituals or propitiations, and even eat with no qualm whatsoever.

A second flaw is that these religions devalue experience that doesn't occur on the "holy days." They implicitly demote days that aren't sabbaths (or Saint's days, or other religious holidays) to a lesser status. You're to observe "the Lord's day" by doing no work, but on your days for doing as you please you can work. The subtext seems to be that you are not to think of "your" days as holy or sacred.

The result seems to be that people live from holiday to holiday, hoping for something transcendent and liberating that never quite comes, for it has been overlooked on all the little, ordinary days, as people have failed to experience and value their lives in themselves, failed to appreciate the sacred in all their ordinary, daily moments. They haven't learned to recognize it because it has been demoted and neglected. The Abrahamic religions have distracted people away from the daily sacred and corrupted their ordinary experience – corrupted their lives – profoundly.

I mention those deficiencies because they are pertinent to the art of treating experience (everyone's and everyday's) as valuable for its own sake – that is, as sacred. But those faults didn't arise in a vacuum; they follow from other defects of the world's Big Three theistic religions:

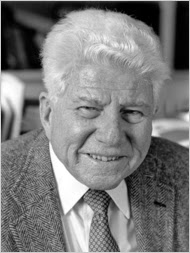

[Note: John E. Smith was the Chairman of the Philosophy Department at Yale when I was an undergraduate there, and my scholarship job for three years was to be his "bursary student." I supported his office staff, made copies, did some research, some typing, that sort of thing. I noted his death in December 2009 ("Death, too, is what happens"). Professor Smith's secretary, who joined the staff a few months after I did, is still on the job, 52 years later. Patricia (Mrs. Alan) Slatter, I salute you! Please give my regards to Alan.]

_______________

Copyright © 2014 by Morris Dean

By Morris Dean

A passage in John E. Smith's study of The Spirit of American Philosophy recently brought me full-stop. It was like the birth of Minerva from my own skull.

The passage was in Chapter IV, on the philosophy of John Dewey, and it was about Dewey's conception of art. It provided a formula or metaphor for me to express my own personal sense of the holy or sacred.

Professor Smith wrote that a trend among twentieth-century thinkers was that

Religion has fallen on evil days, the great moral traditions of Western civilization have been brought into question; science, progress, and the possibilities of history have been made to take their place. But for many this has not been enough. Is there, they have asked, no source of meaning for life which takes us beyond the struggle for existence? Is the whole of life to be summed up in the effort to master ourselves and our surroundings?...We want to go beyond organism and environment, beyond the push and pull of social and political life, to some ideal fulfillment that is more lasting than successful manipulation of things....This passage reminded me that my own, personal view of the sacredness of experience may essentially be an aesthetic view, especially in view of the fact that I have posted a number of "art pieces" in this column. For example, "Perceiving beauty," "Animal spirits," "The sense of life...is life," "Contemplative estheticism: From The Elegance of the Hedgehog." I consider it a sacred art to live in a way that values life and respects one's own and others' experience for its own sake. I accept as self-evident that experience must be valuable for its own sake, for this is it, this is all there is. We pass this way once. Here and gone. We need to cherish it.

...Art as expression....What Dewey called the museum conception of art is to be rejected...it isolates art from experience...and severs the connection between artistic production and ordinary events of aesthetic interest by setting it up on a pedestal. Dewey argued instead for an understanding of art which sees it as a direct development stemming from aesthetic perception; art results from experience and, in a certain sense, is experience. It is experience in that heightened sense in which experience becomes valuable for its own sake. [emphasis mine; pp. 158-9 of the revised edition, 1982]

And it's not just my experience that is valuable. All life on Earth grew out of Earth. I value and respect the experience of others, and include in "others" not only humans but also non-human animals. (They are our relatives, after all.) On this core value is founded my sense of morality, of what is right. It is wrong, for example, to treat a pet, or a farm or ranch animal – or a wild animal – inhumanely, or to end its life unnecessarily. Those animals, too, are in the same situation. For them, too, this is it, this is all there is. Each one passes this way once; each animal is here and gone; it, too, deserves to have and hold its life.

My disbelief in God – and of the supernatural in general – has not left me unreligious in this sense.

One failing of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) is that they don't champion animal rights. They condone the subjugation of animals in general (not to mention out-group humans in particular, whom, for example, they may kill for supposed offenses against their God or His chosen people; whom they may enslave; whose wives they may steal for themselves; whom they may even offer up for sacrifice if they're feeling desperately in need of salvation)....

That is, for these religions, not all experience is valuable for its own sake – certainly not the experience of non-human animals, whom people may sacrifice for their various rituals or propitiations, and even eat with no qualm whatsoever.

The result seems to be that people live from holiday to holiday, hoping for something transcendent and liberating that never quite comes, for it has been overlooked on all the little, ordinary days, as people have failed to experience and value their lives in themselves, failed to appreciate the sacred in all their ordinary, daily moments. They haven't learned to recognize it because it has been demoted and neglected. The Abrahamic religions have distracted people away from the daily sacred and corrupted their ordinary experience – corrupted their lives – profoundly.

I mention those deficiencies because they are pertinent to the art of treating experience (everyone's and everyday's) as valuable for its own sake – that is, as sacred. But those faults didn't arise in a vacuum; they follow from other defects of the world's Big Three theistic religions:

- The Abrahamic religions are founded on fantasies, day-dreams, hallucinations, delusions, fanciful notions, manic visions, wishful thoughts, magical thinking, received myths...that simply aren't true – articulate burning bushes, talking snakes, waging spirits, parting red seas, immaculate conceptions, bodily resurrections, apocalyptic returns, final judgments, heaven, hell, 70-some-odd virgins waiting upstairs to spread their legs for sexually repressed jihadists....

- They promote or condone as moral the treatment of other people and of animals that is actually immoral – human- and other animal-sacrifice (the crucifixion of Jesus was an act of human sacrifice, after all – at least as framed by later Christian writers, who were intent on founding a religion); subjugation of women; "honor" killing of daughters who have sex out of wedlock, consensually or otherwise; outing of gays (contemporary American Christians and Muslims in Africa, Europe, and Asia are warring on gays everyday); covering up sexual abuse of children by clerics (it's still going on in the Roman Catholic Church); accumulation of disproportionate wealth by "chosen" or "elect" people (a popular rallying point for televangelists and mega-business-churches in the United States); rationalization of crimes for which they can be forgiven because "the Son of God died for them," or because they confess, "atone," and do the prescribed number of penances....

- They subjugate followers through fear and intimidation – warnings that if people don't believe certain things they will not go to heaven, or that if they do certain things they will surely burn in hell; the requirement that in order to be pure they do the prescribed number of prayers per day in the prescribed manner and facing in the prescribed direction; threats of stoning or beheading or exile if they don't believe the officially prescribed things; literal judicial executions for apostasy (as Leonard Pitts reports of a current case in Khartoum, in his column "Faith cannot be coerced," in which he writes, "Meriam Yehya Ibrahim...stands convicted of apostasy. She renounced Islam and became a Christian...Converting from Islam is against the law....")....

- They dull the minds of many of their followers with dogmatic poppycock that leaves them unreachable through rationality and science – the earth (the whole universe?) is just over 6,000 years old; Adam & Eve were created in human form and are the parents of mankind; supernatural spirits can intervene willy-nilly in the workings of the material universe, and can either acquiesce in, ignore, or reject the prayers of the faithful (it's the faithful's option to decide which alternative his or her God chose, of course)....

_______________

Copyright © 2014 by Morris Dean

.jpg)

My own core beliefs, and how they differ from the beliefs and practices of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

ReplyDeleteAre you saying live for today, because there is no tomorrow?

ReplyDeleteI do think there may be something after death, but if so, it will be nothing like what is pictured in books. If not, what the hell.

The belief of an after live is based more on the fear of death than in a God.With the finding of something else that offered eternal life as a proven fact, today's religions would lose 90% of their followers. After all with eternal life there is no judgement day.

Ed, no, I am not saying "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you die." That has nothing to do with regarding all experience as "this-is-it sacred." The eat-drink attitude is more a denial of that, it seems to me. The "philosophy of this is it" [so treasure it and don't take it for granted] doesn't mean you don't plan for the future or use your brain to make prudent choices for yourself and others (other animals, human and non-human). In fact, the "this is it" philosophy takes life more seriously, while (it seems to me) the eat-drink philosophy takes it less seriously, devalues it (as the Big Three religions do with their "holy days" nonsense).

DeletePlease tell us why you think "there may be something after death." You even seem to have some conception of it, to be able to say what "it will be nothing like."

Morris, I'm having a hard time pinning down exactly which worldview you are tackling in this (if indeed you intended to hone in on one in particular). You seem to be addressing mainly what you call "Abrahamaic" tradition, but would it be easier to just say your beliefs differ from any worldview that asserts anything supernatural? That is the larger sense I read in this.

ReplyDeleteAs strange as it may sound to you, disbelief in the supernatural is but a tiny part of it. Much more important to me personally, at any rate, is the multitude of problems I have had with the three religions. I tried to enumerate them in the column today. One result of facing and solving them was to become confident in rejecting supernaturalism – not that I ever had a big problem myself with being superstitious or falling into magical thinking. A couple of other results (for example) were to stop attending church and participating in public shows of devotion. I don't bow my head at dinner tables during the saying of "grace" or at city council meetings during the invocations.

DeleteAh, I think I begin to see the root of why you place such relevance on personal experience then. So a disbelief in the supernatural for you isn't an axiomatic assertion at all (as I think it usually is with most philosophers--wouldn't you agree?). Doesn't that open you to sheepishly admitting that any religious folk (claiming an "experience with the Divine" or some such) have equal footing with you in claims of Ultimate Truth? Or is this just a "this is how I see it and it shouldn't affect how anyone else does" post?

ReplyDeleteIt's a little hard to track (for me at least) where your disbelief begins then because you seem to be mixing so many apples and oranges: a bit of Roman Catholicism practice here, some misunderstood Old Testament story there, and even a bit of the Qur'an for poking fun at the zealot strawman of the day. Do you really think those are "equal" in their claims of Truth just because their individual histories at one point involve the same patriarch?

Kyle, thanks for pursuing this; I'm finding it helpful through clarification. The personal experience you cite is not emphasized for epistemological reasons; that is, not as a source of insight into things divine or otherwise. I don't claim to "experience" that there is no God (although I certainly do NOT experience that there is) or that "all is material." I know that many DO claim to know in some direct, personal-experience way that God not only exists but also loves them, listens to them, answers their prayers, forgives them, saves them, etc. My attitude toward that is a respectful acknowledgment that people have the right to such fantasies.

ReplyDeleteMy core-belief valuation of "experience in itself" is not something I know by direct experience, but an intellectual-emotional act that a lifetime of living and thinking have led me to. In fact, I gave my "argument" (or rationale) for valuing experience in itself (not only my own, but yours and other living creatures, including our cousins in the animal kingdom): "I accept as self-evident that experience must be valuable for its own sake, for this is it, this is all there is. We pass this way once. Here and gone. We need to cherish it." I didn't intend "self-evident" in the "axiomatic" sense; I'm not ASSUMING it. I infer it from what follows the coordinating conjunction "for" ("for this is it, this is all there is. We pass this way once. Here and gone. We need to cherish it").

The classification of the Big Three religions as "Abrahamaic" is substantial, not a casual lumping "because their individual histories at one point involve the same patriarch." They are all monotheistic religions, all in thrall to "the one true God." [Wikipedia] (I spent a quarter-hour looking for a post or comment of two or three years ago in which I characterized the invention of monotheism as a tragic mistake, or something like that, but, alas, I couldn't find it.)

My examples from the three religions may seem to you to be "apples & oranges," but I selected them as aptly illustrating the last four major faults / flaws / failures / deficiencies / defects of the Big Three monotheistic religions that I identify.

I found the post I was thinking of: "Beatings will continue" (June 10, 2011), but I don't directly describe or label the invention of monotheism, I just somewhat coyly suggest that it was disastrous enough to earn the Jews the everlasting hatred of Christians and Muslims.

DeleteThis seems a bit circular to me now. The "this is it" axiom leads you to conclude that "experience in itself" is the highest Good. Hence the desire to let all "experiential" creatures thrive for as long as they have on this earth. But then all of this is rooted in, what seems to me, a substitution of the words "intellectual-emotional act" for "experience." So which is it: your axiom leads to your experience, or your experience leads to your axiom? (the latter seems impossible to me).

DeleteI think this line of thinking also runs into the impossibility of answering the question of "why cherish it?" For you, is it that illusory idea of "nobly" soldiering on despite one's imminent and abysmal doom? I've heard Dawkins say something along those lines. Surely you must see that there is no value system that is inherently the highest Good in a world of "this is it." We would all be creating our own subjective Good, and even your own "let all experiential creatures thrive for as long as possible" worldview means no more than anyone else's, and humanity as a whole couldn't work if we all adhered to that.

I can't speak for Judaism or Islam, but I think I can at least address what I think is the heart of your qualm with Christianity insofar as it devalues (as you seem to be putting it) "experience in itself." These were your words: "I mention those deficiencies because they are pertinent to the art of treating experience (everyone's and everyday's) as valuable for its own sake – that is, as sacred."

Christianity is at least mostly in agreement with you. Every human being is imbued with "the image of God," that is to say the power of free agency and personality. Human beings thus are valuable in and of themselves (think of Kant describing us as "ends rather than means") because God has allowed them to share in His existence. Thus, our experience is important because it shares in a simple axiom: God, the highest Good. Human experience is a lesser form (a reflection if you will) of God’s “experience” of the universe, and thus we can call it the highest Good while we live here. Would you not agree that human flourishing is more “important” than beast?

All of the other “flaws” you noted, insofar as they pertain to Christianity, seem to me worthy of individual attention, and that will require more writing in separate threads I think. But hey, I’m off for the summer now, so now I may actually have time for it!

Kyle, this will be just a preliminary response, with more to follow. "This is it" isn't an "axiom," but a fact about the life and death of living things (especially sentient beings - thanks, Dean). Our physical bodies make our sentience possible. After our bodies die, we have no sentience.

DeleteI suppose you consider "this is it" to be an "axiom" because you believe in "life after death" and don't think "this is it" is true. But "this is NOT [all of] it" is actually the "axiom," for, having no evidence for ir, you must assume it (take it on faith).

My experience (and the experience of all sentient beings) just is; it doesn't lead to anything in a chain of reasoning. And no chain of reasoning leads to the experience.

When it comes to an inherently "highest-good value system" for "this is it," Sam Harris has made a defensible statement of one in his book "The Moral Landscape." He identifies the highest good as "the well-being of conscious beings."

More to follow (but perhaps not today).

Kyle, here's that "more to follow":

DeleteYour comment above included the paragraph:

"I think this line of thinking also runs into the impossibility of answering the question of 'why cherish it [i.e., experience - or life - for its own sake]?' For you, is it that illusory idea of 'nobly' soldiering on despite one's imminent and abysmal doom?...Surely you must see that there is no value system that is inherently the highest Good in a world of 'this is it.' We would all be creating our own subjective Good, and even your own 'let all experiential creatures [i.e., sentient beings] thrive for as long as possible' worldview means no more than anyone else's, and humanity as a whole couldn't work if we all adhered to that."

Lots there!

Cherishing something is a personal choice. Many Christians, who presumably have been told clearly by their god what to value as the Highest Good, don't make the same choice I do. Christians, anyway, who also own slaughter houses, sausage plants, or barbecue restaurants - or just consume their products (maybe with a "Thank you, Lord," but with no "I'm sorry" to the animals who made the supreme sacrifice) don't cherish all other sentient beings' lives for their own sake.

...Yet you seem to be implying that their value system is somehow more reliable and more workable for "humanity as a whole"?

Ah! HUMANITY as a whole. So forget the other sentients? (After all, God approves?)

Please explain how "God's approval" (or however you would characterize the basis of valuation) enables a "value system that is INHERENTLY the Highest Good [all-caps mine]."

"Nobly soldiering on"?

Now that you mention it, there DOES seem to be something noble about facing the fact that "this is it" rather that seeking solace in make believe....Is that what you meant?

"One's imminent and abysmal doom...."

Maybe imminent, maybe yet awhile.

Does your view somehow neutralize or render null and void the fact of each sentient's dying and being no more? No belief can make a fact not a fact. Denying something doesn't make it be not so.

"We would all be creating our own subjective Good...."

Well, we all do anyway, don't we? See earlier paragraph about meat-packaging plants or whatever.

Even if all philosophers and scientists were to come to approve Sam Harris's proposal in "The Moral Landscape," millions of individuals would reject it, just as they now reject science or animal rights or equality of women with men, or gays with straights, or blacks with whites, or Mexicans with Americans

The babel of human sentients will not abate.

Well I think we still need to first address this disagreement on the matter of axioms: your saying "'This is it' isn't an 'axiom,' but a fact about the life and death of living things" is to nullify the entire discussion by calling something objective that I don't think inherently is (and perhaps this is where our discussion can go no further if you can't cede the possibility that it isn't an objective fact); "this is it" would require some sort of knockdown proof that nothing happens to our sentience after death. We simply can't know that "scientifically" because it isn't privy to the scope of human observation.

DeleteI would therefore propose that our unique human ability to imagine and reason is proof that there could be sentience after death. Obviously, I don't want you to take that word in its connotative sense that what is "imaginary" is simply “not real.” Rather, human imagination is proof that things that currently are not actually could be. Thus, life after death is certainly a possibility. But then you may perhaps say that all imaginary things may be possible, and that doesn’t get us anywhere. The question then becomes “Is this potential Reality beyond what is material ever involved in what is material?” It would certainly need to be in order for us to gain any traction in further inquiry on the matter. To this, Christianity says yes. Most importantly, it is historically involved—a very specific time, place, and person—in the person of Jesus. The question then becomes one of epistemology: how much are you willing to trust the study of history, and how much of your life are you willing to alter based on that trust?

Lastly, a thought on facts: a fact is a phenomena that simply is just so, regardless of interpretation. The trouble with this is that all things we know as humans are interpretations of phenomena, especially questions of life after death and the supernatural in general. We constantly think in metaphors. It is inescapable, and you perhaps might even call it a very unfortunate product of human evolution. Perhaps you've heard it said that geometry is the only field in which you can truly get knockdown proofs. I would be very hesitant in what we call facts, and thus I may perhaps be as skeptical as you are in your approach to all things, Morris.

Kyle, your latest comment followed my second ["more to follow"] comment by less than an hour, and you don't seem to be addressing anything in it, so I think you were responding to my first ["preliminary"] comment.

DeleteRight, we have a fundamental disagreement over the question of "life [or sentience] after death." And I don't think I can persuade you to accept the "this-is-it fact" by pointing out that technicians ARE privy to (can reliably detect) when there is no longer brain activity in a dead human (or a dead rat), for you seem to hold out for the possibility that something immaterial is in there assisting the brain but whose ghostly activity isn't detectable by the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging machines that monitor the physical activity.

You propose that "our unique human ability to imagine and reason is proof that there could be sentience after death." So...you DENY that sentience after death could be possible for non-human animals? (Does that mean that you find those animals' lives more cherishable than the lives of humans - because they are infinitely shorter than humans' eternal spiritual lives in ineffable heavenly bliss [or insufferable hellish torment]?)

But do YOU have a knockdown proof that "nothing happens to non-human animals' sentience after their death"?

In fact, can you prove that non-human animals can't imagine or reason? Various studies (of I think grey African parrots, dolphins, chimpanzees, dogs, pigs, and elephants) have shown that they CAN.

By the way, if God is all-knowing, how come the scriptures he inspired, don't reflect our current (and future) knowledge of things like this?

You state that "human imagination is proof that things that currently are not actual could be." Uh, no. Some things imagined are actual. Other things imagined can BECOME actual. Other things imagined are purely imaginary, now and ever. Life after death is one of the latter.

No, I'm not willing to concede that "this is it" is not a fact, especially since your position that "this is NOT [all of] it" has considerably more difficulties than "this is it" does.

Plus, the alleged historical evidence of Jesus Christ's resurrection is incredible. Are you familiar with David Hume's argument that for us to accept the report of a miracle as credible, we must find it even more miraculous for the report to be false?

It is very easy not to credit the reports of Jesus's resurrection. To credit them, you have to have a vested interest in their being true. Your (or "one's") desire for everlasting life is a powerful bribe to believe a pitch that promises it.

Morris, you are correct that I was not responding to the post of yours that followed the preliminary comment. I think this conversation naturally branches into more categories than we can tackle at once, so I will try my very best to tackle the primary question of epistemology that (I think) is at the root of this discussion. If we can work through the axiomatic discussion, I think the other discussions will become more profitable since I don't think anything is significant to discuss in Christianity (which you seem to like taking small jabs at on a wide spectrum) if we do not first permit the mere possibility that there is "more" to the universe than the material.

DeleteAgain, to call "this is it" a fact is to assert an objective truth in a plain of discussion that I do not see as objective. You are for more well-read than I am (the advantage of years), so perhaps there is something specific that makes this “fact” plain to you, but I have yet to find it in my own life experience. It looks plainly (to me) like a retreat into “Well I have the Truth regardless of interpretation—says I!” which, again, looks circular. I’m not sure if you meant for this to be taken seriously, but FMRI scans obviously would not monitor non-physical activity, which is what is asserted in any worldview that allows for supernaturalism. It axiomatically denies the possibility of "monitoring" spiritual activity (or whatever you might call it) because it asserts "There is nothing to be known other than through the naked human eye and the instruments humans use to know the universe."

C.S. Lewis actually put what I would say far better than I could in his work Miracles: “If all that exists is Nature, the great mindless interlocking event, if our own deepest convictions are merely the by-products of an irrational process, then clearly there is not the slightest ground for supposing that our sense of fitness and our consequent faith in uniformity tell us anything about a reality external to ourselves. Our convictions are simply a fact about us - like the colour of our hair. If Naturalism is true we have no reason to trust our conviction that Nature is uniform.” I think this addresses quite well your bringing up Hume since Hume’s arguments (if I understand them correctly) are buttressed primarily on the uniformity of human experience. But of course Hume did not have a uniform and complete understanding of human experience. He just had to assume it for the sake of his argument. Like Lewis and other apologists, I don’t see why we should trust atoms bouncing around that somehow create “consciousness” (whatever that is—I’ve yet to hear anyone, scientist or philosopher, give a confident, complete definition).

You also asked for an explanation of how a value system could be inherently the Highest Good based on God’s approval. Rather, I would assert a value system that is the Highest Good based on who God is, that is to say the very nature of His Personhood. I think we, as humans, are accustomed to emulating people as sources of our value systems. So-and-so lives in such a way, and he seems to have it all together; naturally, we want to be like that person. Again, Lewis found that the Personhood of God is what enables us to have any rational understanding of uniformity in the universe (and I think, thereby, a value system). As he put it, “[Our sense of uniformity of experience] can be trusted only if quite a different metaphysic is true. If the deepest thing in reality, the Fact which is the source of all other facthood, is a thing in some degree like ourselves - if it is a Rational Spirit and we derive our rational spirituality from it - then indeed our conviction can be trusted. Our repugnance to disorder is derived from Nature's Creator and ours’.”

I might just be saying the same thing now in different words, so I apologize if this is unhelpful. I at least hope that I am not presenting myself as obstinate or stubborn.

Kyle, I think we're having a very interesting and, for me, productive conversation. Since it's getting involved "enough" with just the two of us, I'm thankful no one else is throwing in his or her small change too!

DeleteI'm dismayed that you think I am "taking small jabs at [Christianity]"; I thought I'd delivered a few walloping uppercuts, roundhouses, and knockdown punches.

Okay, "for the sake of argument" (as they say), I'll "permit the mere possibility that there is 'more' to the universe than the material."

I look forward to your elaborating on what follows from that - aside from deathly opposed religious stances with regard to it. "My Prophet is better than yours." "Your Messiah was no messiah at all, but just a minor prophet; my Prophet brought us God's last word." And so on.

You're right that I was joking about fMRI. It might be detecting everything if there is nothing non-detectable [i.e., supernatural] involved. (But since you think there IS something supernatural involved, then of course fMRI results won't impress you.)

Your quotation from C.S. Lewis on miracles introduces a phrase whose meaning completely escapes me: "our consequent faith in UNIFORMITY [all-caps mine]." What is meant by uniformity, and why must we "have faith" in it rather than know it?

I don't understand uniformity's significance relative to what Lewis is saying OR relative to your [or his] criticism of Hume....

I may be wrong, but you seem to be deliberately avoiding responding to many "points" I'm making. For example: Do you think that non-human animals do NOT have immaterial "minds / spirits / souls"? (I was following up on your seeming to say that humans are unique in that regard.)

Do you think that Christianity DOES champion animals' rights? (If you agree that I am right, it doesn't, is that because non-hunan animals ARE "merely material"?)

And do you object to my characterizing humans as animals? Do you think that God created humans with their current brainpower from their very start?

And finally, with respect to cherishing non-human animals and respecting their right to flourish, do you yourself NOT cherish them (unless they live in your own house perhaps), NOT think they have (or should have) any rights but exist to help humans do work and provide their animal flesh for human gourmandizing and nourishment?

Do you disagree that Christianity, in setting aside "the Lord's Day," devalues the holiness / sacredness of normal everyday days?

In fact, would you mind responding (briefly, in perhaps a single sentence each) to my six allegations of fault with respect to [Christianity specifically; I won't ask you to represent Judaism or Islam too]?

Then we can go on. Thanks.

Kyle, a side thought:

DeleteIn the course of this examination, I have come to realize that the emotion appropriate to valuing other sentient beings' lives for their own sakes is compassion. But, having said that, I realize that "emotion" is not quite the right word...or needs qualification. Whereas sad and mad are emotions, compassion is complex, with what seems to be a moral component. I wish I had thought of mentioning this in the column, in my discussion of the art of treating other lives (other sentients' experience) as sacred, holy - to be valued for their own sake. To grow to have such compassion surely requires learning and discipline...perhaps with some personal suffering. Acquiring an art takes work.

And a further thought:

I suspect that you do not consider it possible for compassion to arise from an entirely material sentient being. Am I right about that?

The New Testament talks about compassion, about agapé, in fact. Is that evidence, for you, that the Bible was "inspired by God"?

However compassion originated, it took root and became a cultural artifact. I'm grateful it did. Sad that it's honored more in the breach than in the application.

Morris,

DeleteI've emailed you my response to the latest. It exceeds the character count that the blog allows, so I couldn't paste it here. Is there any way we can remedy that?

Kyle, alas, the only recourse is to do what I myself have had to do on more than one occasion: post a 2- or 3-parter....

DeletePretty interesting discussion. Makes me think that my view of Buddhism, as I understand some of Buddhism's concepts, avoids most of the difficulties that we find in other religions. Specifically, acknowledgement of the sacred is all "sentient beings."

ReplyDelete"Sentient beings," excellent - the phrase I should have used, because it's what I had (and have) in mind. Sounds as though I need to re- (and better) acquaint myself with Buddihsm. THANKS, DEAN!

DeleteKyle, I'm still hoping to see your latest response. I've been following this with some interest, might even stick my oar in at some point. (Or perhaps not, as The Editor knows my views on these matters all too well.)

ReplyDeleteChuck, Kyle and I are collaborating on a series of articles incorporating his responses to my questions about the "six points," with follow-up interchange to try to reach some agreement, iif only to disagree. We're currently shaping the first, on animal rights, for hopeful.publication on July 3.

Delete